Coined the “Sun Queen” for being a key pioneer in solar energy development, Hungarian-born Dr. Mária Telkes (1900-1995) came to the United States with a hungry appetite and a desire to change the world with her knowledge. With a bachelor's degree and Ph.D. in physical chemistry, she emigrated to the United States in 1925 for a position as a biophysicist in Cleveland, Ohio. Telkes became an American citizen in 1937. Her work would span over fifty years with multiple awards and over twenty patents to her name.

DOVER SUN HOUSE

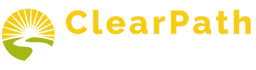

During her time at MIT, Telkes worked in conjunction with architect Eleanor Raymond and designed a solar heating system for an experimental home that would become to be known as Dover Sun House. The Dover Sun House was one of the first houses of its kind to be heated solely on solar energy. The house was completed in 1948 and featured energy storage capacity powered by a process where solar energy is converted through crystallization in a sodium sulfate solution.

Telkes held the hope that this storage system would heat the home for approximately two to three days without sunlight. While this goal was not met, this process was used later on and refined and is now used in a variety of chemical-based heat storage systems. The Dover Sun House was demolished in 2010.

The Dover Sun House and the oil crisis of the 1970s inspired a second experimental home in 1980, the Carlisle House, this time using a photovoltaic (PV) system. Telkes’ work in Dover earned her a spot in developing this second house.

HER INNOVATIONS IN WORLD WAR II :

When the United States entered the Second World War at the end of 1941, the country was put under strict rations of critical materials for citizens to aid in the war effort, making many materials and foods scarce. Energy sources such as gasoline were also included in rationing protocols. This left the United States and the Allies in a precarious situation for supplying much-needed devices for everyday needs while using the least amount of gasoline.

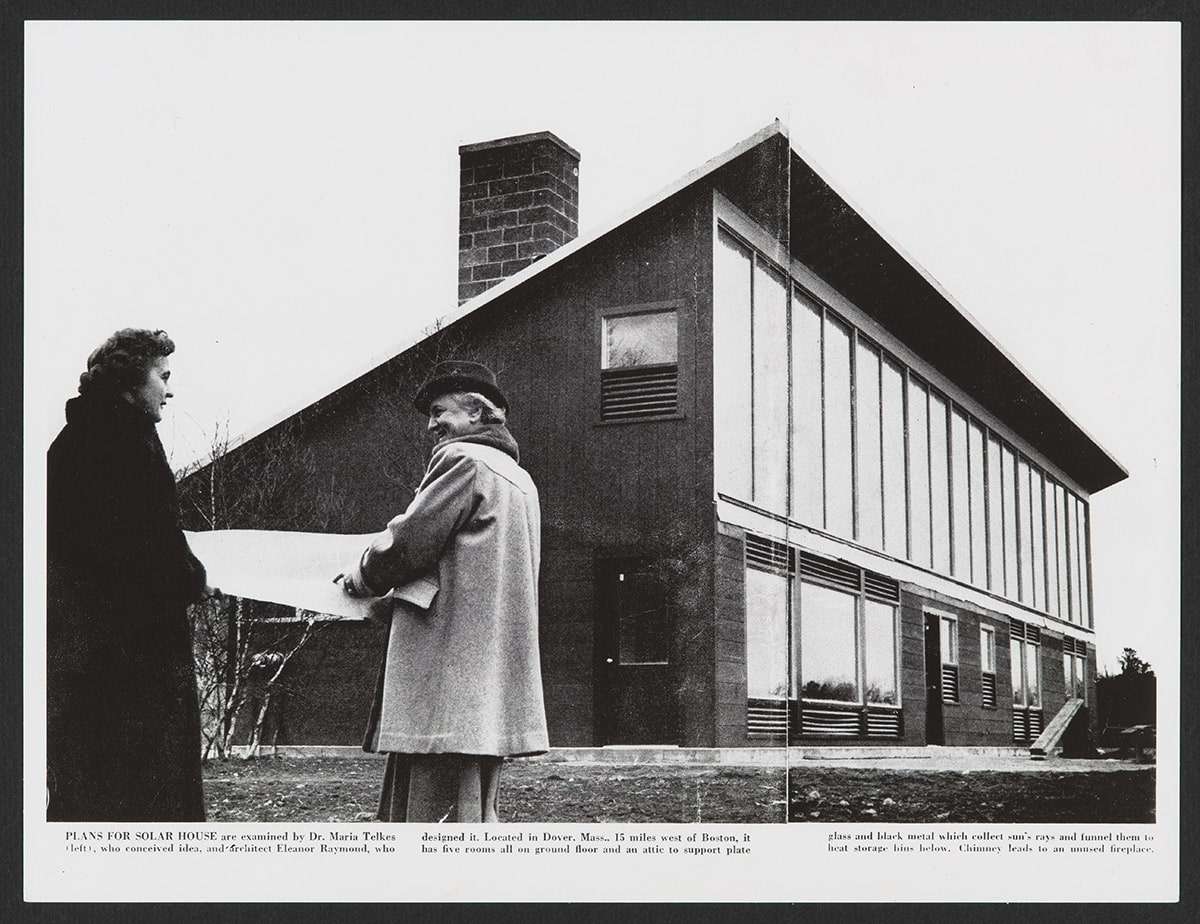

Early on in the United States’ involvement in the war, Telkes joined several other scientists in developing a solar distillation device to be used by soldiers without immediate access to fresh water. The distiller, which was also included in the military’s emergency medical kits, used vaporization to remove sea salt from water and, once cooled, was safe to drink. The system was designed to be scalable and has been used to meet water needs in the Virgin Islands.

CONTRIBUTIONS

While at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Telkes, along with George Washington Crile, created a photoelectric device that recorded brain waves.

While working at Westinghouse Electric as a research engineer, Telkes developed varying instruments to convert heat into electrical energy.

In 1939 Telkes began her research into solar energy and subsequently joined the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to begin work on thermoelectric devices powered by sunlight. She also became an associate research professor in metallurgy at MIT starting in 1945.

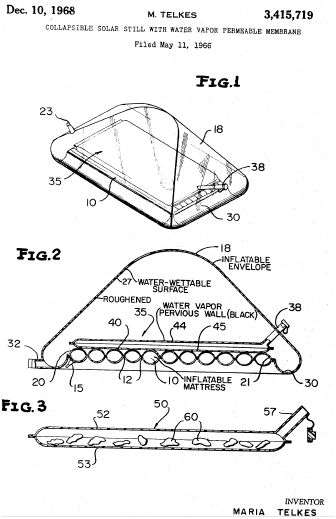

The Ford Foundation commissioned Telkes in 1953 to create an easy-to-assemble solar oven that was safe enough to even be used by children and to cook any type of meal. She was successful and her design reached a temperature high of 350 degrees.

AWARDS

Telkes received several awards for her inventions and owned over twenty patents throughout her life.

In 1952 Telkes was the first to receive the Society of Women Engineers Achievement Award.

In 1977 Telkes received the Charles Greeley Abbott Award from the American Solar Energy Society. Telkes additionally received a lifetime achievement award the same year from the National Academy of Sciences Research Advisory Board for her contributions in solar-heated building technology.

In 2012 Telkes was posthumously inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

PBS’ American Experience has a film about Telkes’ life and accomplishments, which you can watch here.